Your Cart is empty

Subtotal£0.00

Your order details

Your Cart is empty

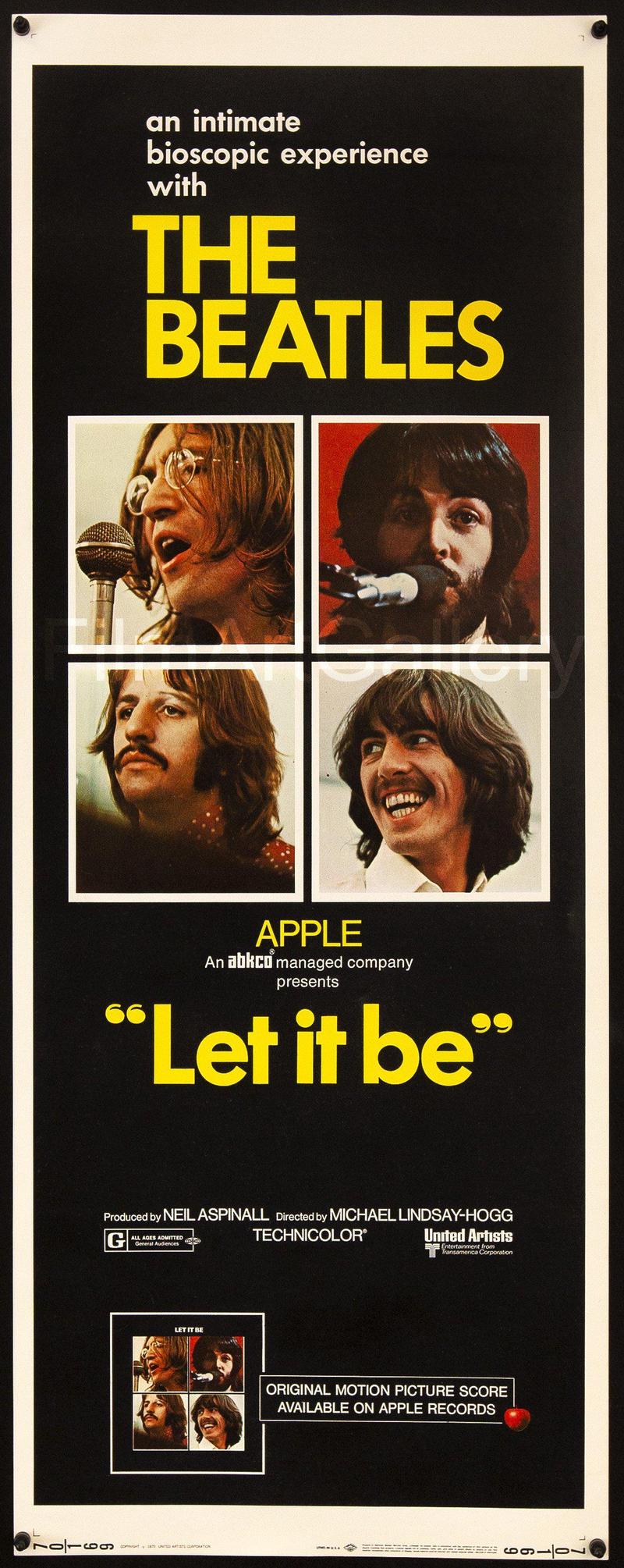

The Beatles got together in January 1969 to film Let It Be, with the intention of making a documentary that would show them rehearsing, building towards a big live show that would be the climax of the movie.

With tensions high within the group, Paul determined that they should return to basics: the live performances that had propelled them to greatness. This belief formed the basis not only of the song Get Back, but the ethos for the documentary in the first part of 1969. But it soon became clear that 1969 was not a rebirth for the Beatles, but the beginning of the end. And as their great career as a band came to an end, so did the Sixties. A new version of the movie is due out soon and purportedly shows the boys in a happier mood than depicted in the original film.

Enthusiasm amongst the band was muted at best when they turned up at Twickenham Studios on the 2nd January to rehearse. The rehearsals were all filmed on 16mm by the director Michael Lindsay-Hogg, with John and Paul overseeing the sound recording and production.

It was clear pretty quickly that it wasn't going to be a smooth process. When in the studio, the band had generally started late in the day and worked deep into the night. For this project, they started at 11am, in a cold and impersonal sound stage. A lot of the playing was uninspired at best, or even sloppy. The Let It Be film gives the overall impression of a band going through the motions.

All the tensions that had simmered through the recording of the white album the previous October - Paul's perceived control-freakery, the presence of Yoko, the patronising of George - boiled over. On January 10, the Friday, George and Paul had a falling out, with George wearily telling his band-mate: "Well I don't mind, I'll play whatever you want me to play. Or I won't play at all if you don't want me to play. Whatever it is that will please you, I'll do it."

He then had a row with John, which reportedly came to blows. George told the others that he had no interest in working on this filmed concert project and wanted to leave the band, and then he went off, memorably telling them "I'll see you round the clubs." He went home, the other three didn't speak; although Yoko did sit on his vacant chair.

They launched into a powerful angry jam accompanied by Yoko shrieking (which must have been nice) and went home for the weekend. They returned on the Monday, and didn't do much of anything, although John apparently mooted the idea of getting Eric Clapton in to play lead.

On the Wednesday George returned for clear-the-air talks. He would stay in the band, on condition that they abandoned the current project of the filmed live gig and instead put the songs on which they had been working into an album.

They left Twickenham for the Apple Headquarters in Savile Row and began recording in there on January 22nd. It was a more productive period: George introduced the American keyboard player Billy Preston into the group, and presence of a stranger seemed to act as a mollifying element for the warring personalities in the group. They recorded a lot of material that would form the basis of the Let It Be album.

The band had discussed venues for a gig including the Roundhouse in Camden, a Roman amphitheatre in North Africa, student unions (!) or even on a cruise ship. But in the end, with all this material for a concert film (and no concert), they decided to play on the roof of the Apple building. George was not keen at all, and Ringo simply refused. However, John and Paul managed to talk them round and, on Thursday January 30th, they took to the roof of the Apple building.

It would be 42 minutes that was not only the Beatles' last-ever live performance, but the end of an era. It's not a brilliant performance per se - would you like to play on a roof on a feezing cold January day? - but it has its moments, on Don't Let Me Down - one of their best and often over-looked songs - and the final Get Back. But it represents something: the final leg of an incredible journey, not only for the band, but the end of the Sixties in many ways. Four working class boys from Liverpool who had not only conquered the world but invented it while they were doing so, returning to their roots - the four piece, bluesy influenced live band that had propelled them to megastardom just a few short years earlier - but finding that there was no way back. They had done all they could.

The first number, a rehearsal of Get Back, is received by the lunchtime crowd with polite applause, perhaps reminiscent of a cricket crowd - Paul mutters something about (England cricketer) Ted Dexter and John jokes: "We've had a request from Martin Luther." They played the song two more times in the short show, including the closing number which was lead into from Don't Let Me Down.

With people on the streets looking up to the skies to find the origin of this music, and others are hanging out of windows, grateful of something to lighten a freezing winter work-day, the police had by now become interested in the gig, and the final version of Get Back takes place against the backdrop of the gig's imminent curtailment by Plod. Some of it is ad-libbed, with Paul signing: "You've been playing on the roofs again, and you know your Momma doesn't like it, she's gonna have you arrested!" The crowd cheer, notably Ringo's wife Maureen - Paul says: "Thanks Mo." John takes the mike: "I'd like to say 'thank you' on behalf of the group and ourselves and I hope we passed the audition!"

They had changed the world. But this was the end. It felt like it. And even now, it still looks like it. Quite upsetting really.